How I Take Photographs

A fellow Instagram photographer who I admire (@rogerevens) suggested that a) I update my blog and b) That maybe I write about how I approach photography.

The first suggestion is definitely a Good Idea; the last post was back in April. Updating websites is what I do all day so updating my own feels like something of a busman’s holiday.

The second suggestion got me thinking. Firstly I am no “great” photographer like Daido Moriyama, who has written a book called How I Take Photographs. The modesty button was immediately pressed. I have an international audience of Instagram followers, but then lots of people do and not all of them are any good.

More importantly, I didn’t actually know how I make photographs. It’s a very instinctive affair, and especially when it comes to street photography where your reaction needs to be quick to capture what you anticipated might happen in the first place. The more I thought about it though, there were themes that emerged.

Why I’m Making the Photograph

This is key to how I approach a shot. For standard street photography, it might just be that a scene has caught my eye, or that the light is playing well in a situation. Basically, it looks nice. But if my aim is more documentary photography - say if I am overseas and want to capture a particular scene, or there’s a detail that explains more of the story, I’ll zone in on that.

Documentary photography has something of a standard narrative to it, if you choose to follow the rules. Start with wide angle, scene setting shots. Hone in on the subjects that are the centre of your study, perhaps with environmental portraits, or something shocking that can help to capture the viewer’s imagination quickly. Embellish these scenes with zoomed in, micro details - perhaps a shot of a hand on rosary beads, or an empty bowl. Whether you follow the documentary rule book or not, making a variety of different shots definitely helps to vary the pace.

It can also be useful to remember to change from landscape to portrait, and vice versa. It’s surprising the number of people I meet who forget to do this.

Go to Interesting Areas

Travel is one of the main reasons I started exploring photography. After a trip to Cambodia where I returned with a lot of half-rate shots, I decided it was time to up my game. So going to interesting areas has always been key to the shots I make. Of course this doesn’t always mean hopping on a plane - there are plenty of interesting areas in every town.

Living in London means I have access to a big city - there’s always an interesting neighbourhood to explore. What’s fascinating to me might not be to you, but I am always interested in how people live, markets, what the markets sell. Maybe an area is known for something - a high Jewish or Afro-Caribbean population, for example. What visually stands out because of this?

Graveyards might not be everyone’s cup of tea, but I find them fascinating as you can chart social history and understand how the location changed over time. We visited one outside Belgrade in Serbia. It was a Jewish graveyard and of course the gravestones stopped in the 1940s (very sad given the memorial to the Jewish soldiers who fought in WW1 in the very same graveyard). Back in London, the Magnificent Seven offer insight into how the city developed during the Industrial Revolution.

Meet People or Hire People

One of the main reasons I use Instagram is that there is a community of like-minded people right there, and all over the world. And whenever I have met any of them in Real Life, they have been unfailingly charming and I have learnt a huge amount from them.

Speaking to local people obviously gives you a layer of insight into a destination that you wouldn’t otherwise have. You might also visit different photographic points that you wouldn’t find by yourself. My husband and son are also grateful for my friends’ intervention: they get terribly bored of me darting off down side alleys, chasing the perfect light or a quirky-looking individual. They are glad to go to the pool for a day by themselves.

Particularly if I am short on time, I might hire a photographic guide for a day. I have enjoyed a number of trips in this way - such as photographing the villagers of Transylvania with @vladbrasov or exploring the alleys of Jerusalem with @simonbeni . There are loads of advantages to this approach. One is that I have picked up innumerable tips on how to use my equipment. One is that they know all of the good spots and can provide the inside track on how to access them. Usually they will also speak the local language and know the people already, which can pave the way to better shots.

I used to feel that hiring people was “cheating” - but of course TV crews and other journalists have been using fixers for years. There are online databases of fixers all over the world. Naturally you have to pay for them - but using them can cut down on the administrative hassle of travelling in a foreign clime and gain you access to subjects that you’d never have plodding the streets by yourself.

Research Your Trip

This one applies more to overseas trips that I make, or trips further away from where I live. While I also like to freewheel and just explore naturally, having an idea of the shots I might want to make does help.

Some trips are entirely inspired by things I have seen or read. For example, a trip to Slovenia was because of Paulo Coelho’s Veronika Decides to Die and my trip to Uzbekistan was entirely due to Eleanor Ford’s excellent cookbook Samarkand. Reading novels around a destination can really augment my imagination and add to my knowledge of a place.

On a more pragmatic basis, I’ll usually read the Lonely Planet or similar, and check out Atlas Obscura. While other photographers with more patience than me take far better shots of tourist sights, it doesn’t mean that I don’t want to see them at all. I’ll research hashtags on Instagram, and Google things that I might want to do. Before the recent trip to Serbia I was researching abandoned building exploration, and reached out to some people who could help me do that. I knew that I wanted shots of the concrete of Novi Beograd, and I knew that the chess players around the fortress would make for good photos. I drop pins on Google Maps and tick them off as I go.

Learn a Bit of the Language and Say Hi

I must admit that I don’t always do this, depending on the destination and how much I have travelled in a specific period of time. Much as I find languages fascinating there is only so much time one has in one’s life. But from a photographic point of view it really does help to be able to say a few words in every language - “OK?”, “Thank you” and so on. And of course communication is rarely just about words. A smile when making a photo of someone can make all of the difference between a good shot and a great one.

Being obvious about your intent when making street photographs really does help. I am a big fan of candid photography, but people do see you. Often I review shots in post-production and realise that the subject has completely seen me the whole time when I thought they hadn’t. Some places are quite anti their photos being taken (Serbia), and some places are very welcoming (Myanmar). Sometimes I carry a small portfolio book which explains what I do, and usually I’ll have some business cards on me that I hand out if people want to get the photo later. It takes a bit of guts, but asking people for shots also leads to superb work - there are those that love the camera and are more than happy to pose. Being able to communicate is key to all of this.

Walk, and Then Walk Some More

One of the reasons I like photography is that I like walking. Which is fortunate, because I do a lot of it (during a week in Belgrade I easily clocked up over 100km). Apart from the visual side of things, walking is a great way to really experience a place with more than just your eyes. You smell the smell of food cooking, you hear the sounds of everyday life. It also keeps me fit.

I have been known to take shots out of car windows - in our family we call this “car tourism”. But there’s no substitute for walking down a street and seeing what’s happening - and then walking back the other way. I always miss something the first time. Look up at the windows or the sky, and look down at the pavement. Go back at different times of the day, when the light falls differently or when you’re in a different kind of mood. The shots will always be different.

Telephoto Lenses or Prime?

Personal choice this one but the lens that works for me is an 18-135mm. It allows me to zoom closer to subjects I can’t reach with a prime and allows me greater flexibility while travelling. It also means I don’t have to pack a whole bag of heavy gear (done that).

Look for the Light (and the Shadow)

Unlike many photographers, I don’t mind shooting in the full glare of the midday sun. Apart from anything else, shooting at Golden Hour only would mean severe restrictions on how much I could explore. Shadow play always makes for an interesting shot - I look for a dark background (a shop doorway, or recently I took a picture of someone in front of a lake) and create the contrast with the light hitting the subject in front.

Shooting with other photographers has made me much better in this respect. We learn from each other, and I have found the community very generous with their knowledge. Seeing what catches another person’s eye also helps to educate on what could catch yours, too.

Curious People (and Be Curious)

Photography is social anthropology, and being curious about people really helps my photography. The lens never judges; it just captures. In far-flung climes, of course everyone is curious. Somebody doing their laundry in Indonesia is far more interesting than me loading up my Samsung with the week’s dirty sheets. What are they eating? How are they eating it? What are the customs of that area? For example, in Cambodia they chuck their toothpicks on the floor after eating, so that they get swept up hygienically (maybe this has changed since coronavirus, but certainly used to be the case).

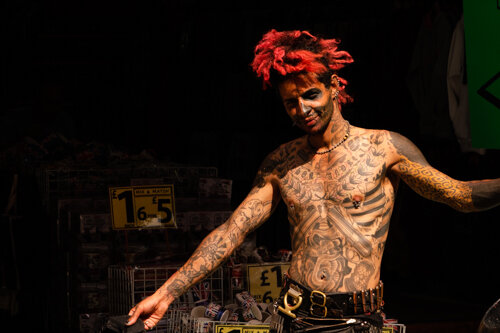

Closer to home, cities always provide “characters”. The less conformist the dress, the more likely the subject is to willingly provide shots. I look for unusual dress, or perhaps clothing that stands out against the surroundings. And of course there is always the chance of a witty juxtaposition against an advertising hoarding or one of those shots that come from pure serendipity. You know when you’ve got one.

Cats

Finally, no photography trip in complete without a picture of a cat or two. Be kind to them, they are the future ;)

Photographic Objectivity in Documentary Photography

Combining the last weeks of documentary photography study with field practice, shooting in a retirement home, I consider what it means to be truly objective as a photographer - and whether it’s possible at all.

Over the few weeks that I’ve been attending this course at City Lit, we’ve touched upon the subject of objectivity a number of times, and especially as it relates to photography.

What Does This Mean?

As with all subjects that get mired with academia, there are numerous definitions of what objectivity means in photography. When I looked up the subject on the Internet, I found a good article by a guy called Steve Middlehurst. He says,

“In Photography (1) Stephen Bull offers a definition of objectivity and subjectivity. He says that photographic objectivity is when the object, or subject matter, in front of the camera produces the photograph whereas photographic subjectivity is when the photographer, the subject behind the camera, has produced the photograph.”

In my field, ecommerce, there is an old but oft-quoted textbook by a guy called Steve Krug, called Don’t Make Me Think. The point is that, in Internet design, if a customer has to think about how they do something online, it’s just not simple enough. And that’s how I feel about that quotation. While I may be missing the point, even thinking about that quotation leaves me a bit confused. How would I tell if a photographer or an object has produced the photograph?

So, as I see it now, this is my Simpleton’s Guide to Photographic Objectivity.

Has the photographer taken the shot candidly, or with the knowledge of the subject (if the subject is alive)?

Has the photographer altered the composition in any way? For example, have they asked the subject to pose in a particular way? Have objects in the room been moved? Is the entire scene staged?

Has the photographer altered the photograph with post-processing (be this digital or with more old-fashioned dodging and burning techniques)?

When was the photographer shooting? What equipment were they using? What were or are the constraints around this? For example, in the early days of the photograph exposures were long and those candid moments were harder to capture

Has the photographer captured a one-off shot, or have the images been gathered over a period of time?

Has the photographer been paid by a particular organisation to portray a particular point of view? Have they embarked to illustrate a point or idea, or have they concluded the photographic essay with what they found along the way?

What is the photographer’s motivation (if not paid)? Here we looked at the work of Lewis Hine, a campaigner against child labour in the United States. While the motivation may be intrinsically benevolent, it is still introducing - nay forcing - bias into the photographic process and into the minds of the viewer. In effect, it’s propaganda

Has the photographer’s work been censored in any way? Typically we think of censorship as part of repression or wartime - you could argue it’s also part of the editorial process, of curation. A friend of mine took a selection of pictures for a documentary project, and the participants selected the shots. This is a beautiful community action, one that I really like, but did the participants “hold a mirror up to nature” - or select the shots that they believed most flattering?

Finally, a topic we haven’t touched on in class, and that is the photographer’s relationship to the subject. Taking some shots in a retirement home at the weekend, where my aunt is resident, I didn’t expect to be so overcome with my own emotion.

Should a photographer shoot subjects that are “close to home” or do they give away their objectivity in doing so? Is it ethically right to photograph people we know really well? Or is the photographic bias blown away from the outset?

Furthermore, it’s clear that the process of visually documenting aspects of life can be truly shocking. Some of the most remarkable documentary photos pivot on this - for example, the war photography of Don McCullinn. While you can hardly equate going in an old person’s home with entering a war zone, the experience did make me think about the kind of documentary projects I want to shoot. Feeling emotion is a powerful tool to creating emotion in others - but how much is too much for the photographers themselves? And how do you know when you’re about to cross that invisible line?